Vini spumanti secchi italiani 2025 : Le “Cinque Sfere” e le tendenze del settore nella nuova guida SPARKLE

di Cristina Santini

Quest’anno, l’atmosfera di festa pervade tutti noi con l’apertura della ventitreesima edizione di Sparkle 2025, evento curato da Francesco d’Agostino, direttore responsabile della Rivista Cucina & Vini, che celebra il 25° anniversario della pubblicazione.

“Nel 1999, un gruppo di amici sommelier ha lanciato l’idea di creare una rivista nazionale, spinti dalla passione e da uno spirito giocoso. Venticinque anni fa, mia moglie Alessandra Marzolini e io abbiamo fondato questa pubblicazione. Nel tempo, il gruppo è cresciuto, concentrandosi principalmente sul vino, e il numero di sommelier è aumentato sotto la sua guida. A un certo punto, la nostra passione è diventata così forte che abbiamo deciso di rilevare la rivista e farla nostra.”

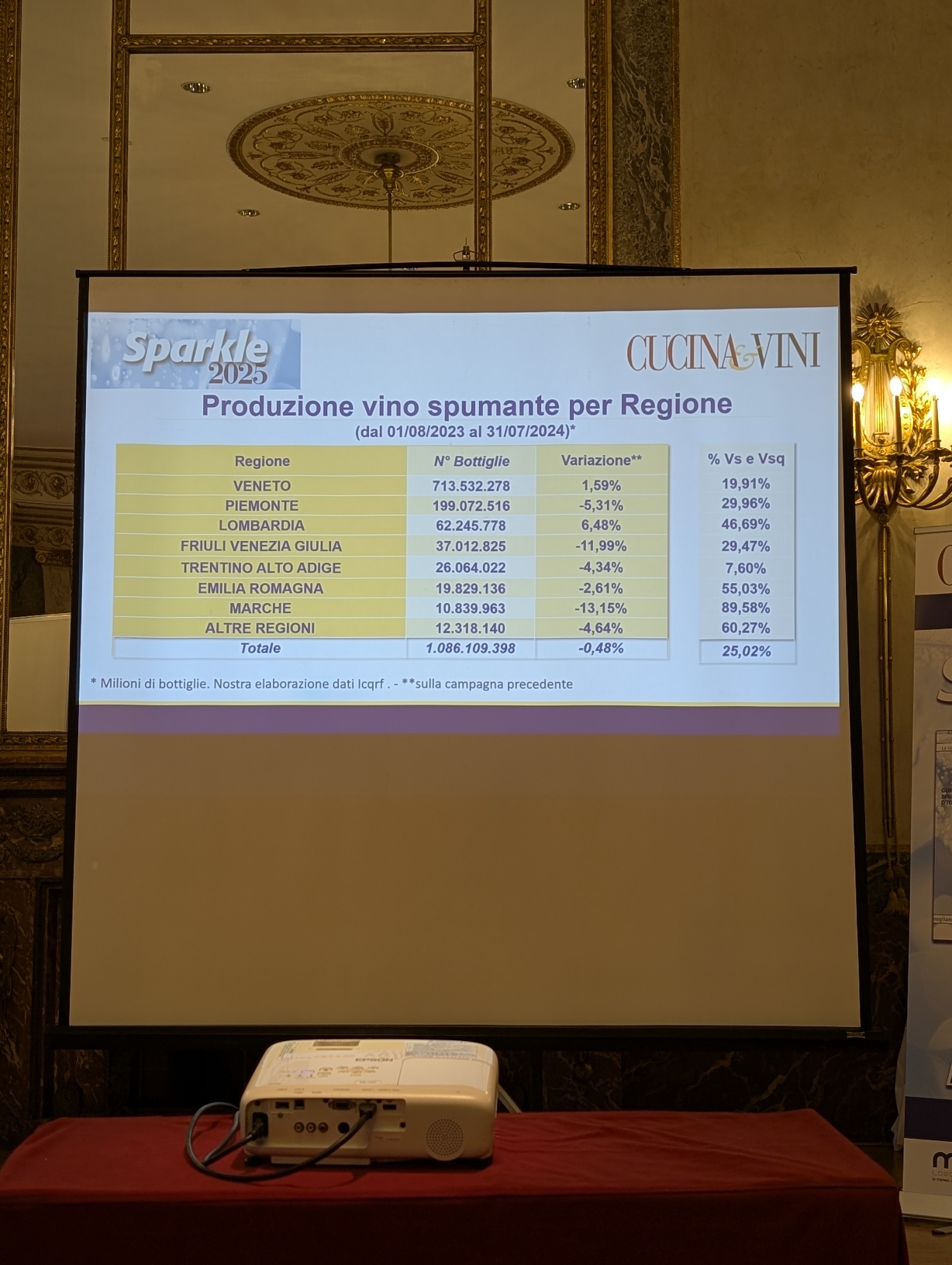

“Sparkle” è l’occasione perfetta per esplorare il mondo degli spumanti e discutere del presente e del futuro di un fenomeno che conta oltre un miliardo di bottiglie all’anno. I dati dipingono un quadro positivo: i numeri parlano da soli e le cifre delle esportazioni per questa categoria di vini continuano a crescere in modo incoraggiante. La produzione sta crescendo, superando le vendite, indicando una prospettiva ottimistica tra i produttori.

Nonostante sia l’unico vino in crescita negli ultimi dieci anni, il consumo rimane stabile nei mercati tradizionali ma è in calo in patria (ne consumiamo meno ogni anno). Tuttavia, ci sono alcuni aspetti critici nel riepilogo di quest’anno.

Francesco D’Agostino ha continuato, notando due tendenze distinte. Nei distretti spumantistici del nord, la produzione continua a vedere una crescita media sostanziale, in particolare nell’intera regione subalpina e nelle zone principali. D’altro canto, è curioso che la produzione di vini Spumante VS e VSQ stia crescendo anche in tutta Italia, sebbene l’aumento sia più pronunciato nelle aree in cui possono essere utilizzate più denominazioni, il che è un dato interessante.

Utilizzare prodotti di dubbia qualità senza alcun legame a una denominazione per raccontare il proprio spumante comporta un rischio elevato. Sebbene in questo caso il brand aziendale possa prevalere, ciò non è sufficiente. Oggi è necessario creare gruppi coesi, con membri identificati da nome e cognome, che condividano un legame con il territorio.

Ci sono preoccupazioni critiche riguardo il prossimo Decreto sui vini dealcolati. Questo mercato in espansione potrebbe portare a un grande business per i vini italiani senza denominazione di origine (come DOCG, DOC e IGT), che rappresentano una grossa fetta del settore. Sebbene sia giusto soddisfare la domanda dei consumatori, è necessario codificare attentamente questi prodotti e, allo stesso tempo, difendere le altre categorie di vini di qualità.

Il direttore afferma che è una questione estremamente critica il fatto che alcune nazioni, come la Francia, vendano vini spumanti dealcolati a prezzi esorbitanti e che le persone li acquistino effettivamente. Questa situazione richiede che i distretti dello spumante facciano sforzi ancora maggiori per enfatizzare la loro identità unica. Il rischio è che i consumatori non si rendano conto che il prodotto che viene loro venduto ha un profilo basso ma ha un prezzo elevato semplicemente perché porta un marchio forte.

Inoltre, anche il mercato italiano è pronto a essere inondato da questi prodotti, il che dovrebbe spingere i nostri produttori a impegnarsi in una profonda riflessione.

È necessaria anche una comunicazione più chiara ed energica, poiché manca una vera cultura del Prosecco, ad esempio. Tutto viene banalizzato e ridotto semplicemente alla parola “Prosecco”, che invece andrebbe identificata con la lettera maiuscola per sottolinearne l’importanza come denominazione di un territorio specifico. È fondamentale far comprendere bene questo aspetto.

Il 30 novembre è stata presentata al The Westin Excelsior Hotel di Roma la 23a edizione della guida SPARKLE 2025 ai migliori vini spumanti secchi nazionali. Diamo un’occhiata più da vicino ad alcuni dati chiave sulla produzione dei vini italiani presenti in questa guida.

Gli ultimi dati ICQRF (Ispettorato centrale della tutela della qualità e della repressione frodi dei prodotti agroalimentari) sulla stagione di produzione vinicola 2023/2024 confermano una produzione stabile e una situazione eccellente sia per i vini Metodo Classico che per quelli Metodo Martinotti, comprese le annate degli ultimi due o tre anni.

Una statistica curiosa è che il 25,02% della produzione totale è costituito da vini senza nome (Vino Semplice e Vino Spumante di Qualità), con una percentuale ancora più alta nelle regioni del Centro-Sud. Tuttavia, questa tendenza potrebbe giustificare una revisione per considerare l’utilizzo di Indicazioni Geografiche o altre denominazioni.

In termini di produzione (numero di bottiglie), i dati più notevoli sono i cali per Asti DOCG (-13,96%), Conegliano Valdobbiadene DOCG (-4,84%) e Alta Langa (-3,97%). Sorprendentemente, il Prosecco DOC, il vino più prodotto in Piemonte, ha superato negli ultimi anni l’Asti, rinomato a livello mondiale, registrando un aumento del 2,31%. Nel frattempo, Asolo DOCG continua a crescere costantemente (23,34%), così come Franciacorta DOCG (17,40%), mentre Trento DOC sta vedendo un progresso più graduale del 2,94%.

I dati ufficiali ISTAT che confrontano le esportazioni 2020/2024 sono incoraggianti. Il valore delle esportazioni è cresciuto in modo significativo in questo periodo, da 1.473 milioni di euro nel 2020 a 2.378 milioni di euro ad agosto 2024. Analogamente, il numero di bottiglie esportate è aumentato da 544 milioni nel 2020 a 741 milioni nel 2024.

Tuttavia, mentre la crescita del volume delle bottiglie ha superato la crescita del valore delle bottiglie, indicando una leggera diminuzione del valore medio per bottiglia. In altre parole, i volumi di produzione ed esportazione sono in aumento, ma il prezzo medio per bottiglia è diminuito leggermente.

Nel complesso, i dati indicano una sana crescita delle performance delle esportazioni dell’Italia nel periodo 2020-2024.

La Guida di quest’anno presenta alcuni numeri interessanti:

• 937 i vini selezionati, con 68 etichette in più della passata edizione;

• ancora una volta la regina indiscussa è la Lombardia (339 vini), seguita da Veneto (260), Trentino (131), Piemonte (86);

• le Denominazioni che governano questa dinamica sono aumentate rispetto allo scorso anno e sono la Franciacorta con 273 vini, Conegliano Valdobbiadene con 237, Trento con 129 e l’Alta Langa con 68;

• I premi assegnati quest’anno includono 87 ambitissime sfere d’eccellenza, un traguardo importante e un obiettivo da mantenere nel tempo. La Lombardia è ancora una volta in testa con 33 allori, seguita dal Trentino con 19, dal Veneto con 16, dal Piemonte con 7, dall’Alto Adige e dall’Abruzzo con 3 ciascuno, dalla Puglia con 2 e dal Friuli Venezia Giulia, dalla Toscana, dal Lazio e dalla Sicilia con 1 sfera ciascuno.

Continua ad essere decretato, per la ventunesima volta, il “vino dell’emozione”, ovvero quel vino che seduce, il più emozionante ma non il super 5 sfere, che segue criteri di giudizio soggettivi e non fisiologici del gusto.

Premiato a Sparkle 2025 il Franciacorta Riserva Nobile Alessandro Bianchi Rna 15 anni Extra Brut 2007 di Villa Franciacorta.

La Guida è inoltre arricchita dalla bacheca “Cinque Sfere”, che elenca le migliori aziende vinicole premiate che esemplificano la produzione costante e l’eccellenza delle migliori case spumanti italiane. Inoltre, c’è una sezione “acquisto attento” che presenta i vini con il miglior rapporto tra valutazione della guida e prezzo e una classifica che mostra le aziende che hanno ottenuto il maggior numero di riconoscimenti nel corso della storia di Sparkle.

La sezione “il tempo del vino” della degustazione “Vintage”, dedicata alle vecchie annate, offre un modo meraviglioso per comprendere l’evoluzione di un vino. Immergendosi completamente nel piacere, nella curiosità e nella scoperta di un mondo sconfinato, si può assaporare il vino senza impantanarsi in troppi tecnicismi. Grazie agli anni di esperienza maturata, Sparkle si è affermato come una guida ricca e affidabile nel variegato mondo degli spumanti italiani. Il suo volume è una lettura imprescindibile e un riferimento essenziale per orientarsi in questo effervescente settore.

Ecco l’elenco completo delle “5 Sfere” di Sparkle 2025 suddivise per Regione:

PIEMONTE

• Alta Langa Bianc ’d Bianc Brut 2018 Giulio Cocchi

• Alta Langa TotoCorde Brut 2018 Giulio Cocchi

• Alta Langa Riserva Zero 140 Pas Dosé 2010 Enrico Serafino

• Alta Langa Riserva Zero Pas Dosé 2018 Enrico Serafino

• Alta Langa Riserva Cuvée 60 Mesi Brut 2013 Gancia

• Soldati La Scolca D’Antan Brut 2012 La Scolca

• Soldati La Scolca D’Antan Rosé Brut 2012 La Scolca

LOMBARDIA

• Franciacorta Satèn Edizione 2020 Barone Pizzini

• Franciacorta Pas Operé Extra Brut 2018 Bellavista

• Franciacorta Riserva Palazzo Lana Extrême Extra Brut 2013 Guido Berlucchi

• Franciacorta Rosé Extra Brut 2020 Bosio

• Franciacorta Riserva Cuvée Annamaria Clementi Dosage Zéro 2015 Ca’ del Bosco

• Franciacorta Riserva Cuvée Annamaria Clementi Rosé Extra Brut 2015 Ca’ del Bosco

• Franciacorta Riserva Vintage Collection Dosage Zéro Noir 2015 Ca’ del Bosco

• Franciacorta Nero Zero 2019 Colline della Stella

• Franciacorta Blau Blanc de Noir Extra Brut 2016 Corte Aura

• Franciacorta Riserva Raramè Dosaggio Zero 2012 Corte Aura

• Franciacorta Rosé Brut Corte Fusia

• Franciacorta Le Millésime Brut 2015 Derbusco Cives

• Franciacorta Riserva 33 Non Dosato 2016 Ferghettina

• Franciacorta Riserva Extra Brut 2016 Ferghettina

• Franciacorta Satèn 2020 Freccianera Fratelli Berlucchi

• Franciacorta Riserva Capitolo II Dosaggio Zero 2016 Le Vedute

• Franciacorta Superno Dosaggio Zero 2016 Marzaghe

• Franciacorta Satèn 2020 Mirabella

• Franciacorta Satèn 2020 Mosnel

• Franciacorta Riserva Villa Crespia Millè Brut 2014 Muratori

• Franciacorta Satèn 2020 Tenuta Ambrosini

• Franciacorta Ricciolina Satèn Terre d’Aenòr

• Franciacorta Rosé Extra Brut 2020 Terre d’Aenòr

• Franciacorta Comarì del Salem Extra Brut 2017 Uberti

• Franciacorta Dequinque Cuvée 15 Vendemmie Extra Brut Uberti

• Franciacorta Magnificentia Satèn 2020 Uberti

• Franciacorta Cuvette Brut 2019 Villa Franciacorta

• Franciacorta Diamant Pas Dosé 2019 Villa Franciacorta

• Franciacorta Riserva Nobile Alessandro Bianchi Rna 15 anni Extra Brut 2007 Villa Franciacorta

• Oltrepò Pavese Metodo Classico Pinot Nero Riva Rinetti Pas Dosé 2019 Calatroni

• Oltrepò Pavese Metodo Classico Pinot Nero Dasdòt Pas Dosé 2019 Fradé

• Lugana Brut Nature 2013 Perla del Garda

• Mattia Vezzola Grande Annata Brut 2018 Costaripa

TRENTINO

• Trento Riserva Collezione Luciano Lunelli Rosé Brut 2009 Abate Nero

• Trento Riserva Graal Brut 2017 Altemasi

• Trento Brut Balter

• Trento Riserva Pas Dosé 2017 Balter

• Trento Riserva 907 Extra Brut 2018 Cantina di Isera

• Trento Riserva Brezza Riva Pas Dosé 2019 Cantina di Riva

• Trento R Rosé Brut Cantina Rotaliana

• Trento Riserva R Brut 2016 Cantina Rotaliana

• Trento Riserva Oro Rosso Dosaggio Zero 2018 Cembra Cantina di Montagna

• Trento 1673 Rosé Brut 2017 Cesarini Sforza

• Trento Riserva Lunelli Extra Brut 2016 Ferrari Trento

• Trento Riserva Masnen-Vignal Blanc de Blancs Extra Brut 2019 Klinger

• Trento Riserva del Fondatore 976 Brut 2013 Letrari

• Trento Riserva Dosaggio Zero 2019 Maso Martis

• Trento Brut Nature 2018 Moser

• Trento Riserva Tracce Extra Brut 2011 Moser

• Trento Riserva Flavio Brut 2016 Rotari

• Trento Maso Nero Dosaggio Zero 2019 Zeni

• Trento Riserva Maso Nero Blanc de Noir Extra Brut 2017 Zeni

ALTO ADIGE

• Alto Adige Riserva Extra Brut 2018 Arunda

• Alto Adige Riserva 600 Blanc de Blancs Extra Brut 2018 Cantina Kurtatsch

• Alto Adige Riserva 1919 Extra Brut 2018 Kettmeir

VENETO

• Asolo Prosecco Superiore Extra Dry 2023 Commendator Pozzobon Rosalio

• Valdobbiadene Rive di Colbertaldo Vigneto Giardino Asciutto 2023 Adami

• Valdobbiadene Rive di Santo Stefano Dirupo Nazzareno Pola Etichetta del Fondatore Extra Dry 2023 Andreola

• Valdobbiadene Rive di Soligo Mas de Fer Extra Dry 2023 Andreola

• Valdobbiadene Superiore di Cartizze Dry 2023 Andreola

• Conegliano Valdobbiadene Prosecco Superiore Rive di Soligo Extra Brut 2023 BiancaVigna

• Valdobbiadene Prosecco Superiore BandaRossa Vigna di Collagù Extra Dry 2023 Bortolomiol

• Valdobbiadene Prosecco Superiore Ius Naturae Brut 2023 Bortolomiol

• Valdobbiadene Coste di Mezzodì Dry 2023 Col Vetoraz

• Valdobbiadene Rive di Vidor Tittoni Dry 2023 La Tordera

• Valdobbiadene Prosecco Superiore Cruner Dry Le Colture

• Conegliano Valdobbiadene 20.10 Extra Dry 2023 Le Manzane

• Valdobbiadene Prosecco Superiore Extra Dry Rebuli

• Valdobbiadene Prosecco Superiore Rive di Farrò Particella 232 Extra Brut 2023 Sorelle Bronca

• Lessini Durello Riserva Amedeo Évolution Pas Dosé 2012 Ca’ Rugate

• Lessini Durello Riserva Amedeo Pas Dosé 2018 Ca’ Rugate

FRIULI VENEZIA GIULIA

• Dom Jurosa Blanc de Blancs Extra Brut 2018 Lis Neris

TOSCANA

• Bolle di Borro Rosé Brut 2018 Il Borro

LAZIO

• Alarosa Rosé Brut Vigne del Patrimonio

ABRUZZO

• Nicola Di Sipio Brut Di Sipio

• Brut Marramiero

• Rosé Brut Marramiero

PUGLIA

• Daunia Bombino Bianco RN Brut 2019 d’Araprì

• Gianfranco Fino Rosato Dosaggio Zero 2019 Gianfranco Fino

SICILIA

• Etna Gaudensius Blanc de Noir Brut Firriato

Sito di riferimento: https://www.cucinaevini.it/guida-sparkle/

Siti partners articolo: https://carol-agostini.tumblr.com/ https://www.papillae.it/ https://www.foodandwineangels.com/

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.